Introduction: The Garage Fallacy

In 1938, two Stanford graduates named Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard tossed a coin in a Palo Alto garage to decide whose name would come first on their fledgling electronics company. Hewlett won the toss, and Hewlett-Packard was born—a story so etched into Silicon Valley lore that garages have since become shorthand for entrepreneurial genius. But here’s the twist: Hewlett and Packard didn’t work alone. Their first product, an audio oscillator, was engineered with feedback from Walt Disney Studios, which needed the device to perfect the sound in Fantasia. Their garage was less a solitary lab than a crossroads, where mentors, clients, and collaborators drifted in and out, shaping an idea into an empire.

This is the paradox of entrepreneurship: We celebrate the myth of the lone visionary while ignoring the scaffolding that holds them up. The truth is, what revolves around being an entrepreneur is not a singular genius, but a constellation of relationships, borrowed wisdom, and cultural timing. Consider the numbers: A 2023 analysis of Fortune 500 founders found that 85% launched their companies with co-founders or a core team. Even Steve Jobs—the patron saint of solo genius—relied on Steve Wozniak’s engineering prowess and Mike Markkula’s business acumen to turn Apple into a behemoth. Entrepreneurship, it turns out, is less about building something from nothing than about assembling a jigsaw puzzle where the pieces are scattered across people, places, and moments in time.

Why does this myth persist? Because stories of individual triumph are easier to digest. They fit neatly into TED Talks and LinkedIn posts. But to understand what truly drives entrepreneurial success, we must venture into the messy, collaborative reality behind the curtain—a world where networks matter more than notebooks, and where the best ideas are often stitched together from borrowed threads.

The Myth of the Lone Visionary

1. The Edison Delusion: How History Rewrites Collaboration

Thomas Edison is often remembered as the solitary “Wizard of Menlo Park,” hunched over a lab bench as he willed the lightbulb into existence. But Menlo Park was not a wizard’s lair—it was an innovation factory. Edison employed 60 engineers, machinists, and physicists he called “muckers,” who worked in shifts around the clock. His genius lay not in solo invention, but in managing what historian Robert Friedel calls a “collision of specialties.” The carbonized bamboo filament that made his bulb viable? It was suggested by a mucker who’d studied Asian textiles.

Edison’s real breakthrough was organizational, not technical. He created the first industrial R&D lab, a model later copied by Bell Labs and Xerox PARC. Yet history collapsed this sprawling effort into a single name, perpetuating the myth that innovation springs fully formed from individual minds.

Why It Matters:

- The “Credit Assignment” Problem: A 2021 study in Nature found that 92% of patented inventions are improvements on existing ideas, yet 78% are attributed to lone inventors in media.

- The Network Effect: Entrepreneurs embedded in professional networks are 3x more likely to pivot successfully after failures (Harvard Business School, 2020).

2. The PayPal Mafia: When Disagreement Becomes Fuel

In 1998, a group of six co-founders—Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Reid Hoffman, and others—launched a fintech startup called Confinity. It later merged with Musk’s X.com to become PayPal. After PayPal’s $1.5 billion sale to eBay, this group, dubbed the “PayPal Mafia,” went on to fund Tesla, LinkedIn, YouTube, and SpaceX. Their secret? They fought—relentlessly.

Thiel recalls, “We disagreed on everything: the user interface, the revenue model, even the company name. But those arguments forced us to pressure-test ideas until only the strongest survived.” Musk and Thiel once clashed so fiercely over coding priorities that Musk temporarily left the company. Yet this friction became their competitive edge.

The Science of Creative Conflict:

- A 2019 MIT study found that teams with “task-oriented conflict” (debating ideas, not personalities) produced 40% more patents than consensus-driven groups.

- Cognitive diversity—differences in how people think—accounts for 35% of a team’s innovation capacity (Forrester Research).

Takeaway: The PayPal Mafia didn’t succeed despite their disagreements; they succeeded because of them. Entrepreneurship thrives on constructive friction, not harmony.

3. The Mentor Paradox: Why Outsiders See What You Can’t

In 2000, Sara Blakely, a 29-year-old fax machine saleswoman, spent $5,000 to patent an idea she’d sketched on a napkin: footless pantyhose. But she hit a wall when manufacturers dismissed her as a “nobody with no fashion experience.” Then, over coffee, a stranger asked her, “Have you thought about Oprah? If she likes it, you’re golden.” Blakely hadn’t. Six months later, Oprah named Spanx her “Favorite Thing” of 2001, and Blakely became the youngest self-made female billionaire.

That stranger was a retired hosiery executive who’d seen dozens of startups fail. His advice wasn’t revolutionary—it was obvious. But to Blakely, mired in the weeds of prototypes and patents, it was a revelation.

The Hidden Power of “Cognitive Outsiders”:

- Mentors act as “pattern interrupters,” jolting founders out of tunnel vision. A 2022 Stanford study found that mentored entrepreneurs spot market opportunities 25% faster.

- The best mentors are often outside the founder’s industry. Spanx’s advisor came from textiles, not fashion.

Case Study: Y Combinator’s “Office Hours”

Paul Graham, co-founder of Y Combinator, structured the accelerator’s mentorship around a simple rule: “Founders get 10 minutes with someone who knows nothing about their business.” Why? Fresh eyes spot flaws insiders overlook.

4. The Tribal Mindset: How Ecosystems Replace Genius

Silicon Valley’s rise wasn’t driven by lone coders in garages—it was fueled by a tribe. In the 1950s, Frederick Terman, Stanford’s dean of engineering, lured Defense Department contracts to the area, creating a feedback loop between academia, government, and industry. By the 1970s, engineers at Fairchild Semiconductor—the “Traitorous Eight”—split off to launch Intel, AMD, and Kleiner Perkins, creating a dense web of talent and capital.

The “Silicon Valley Effect”:

- Proximity matters. Startups within 1 mile of venture capital firms raise funding 20% faster (National Bureau of Economic Research).

- Ecosystems act as “idea accelerators.” A founder in Silicon Valley hears about new trends 6–8 weeks before those in isolated regions (McKinsey & Co.).

The Counterexample: Detroit’s Decline

In the 1960s, Detroit accounted for 50% of global car production. But its insular culture—executives lived in Grosse Pointe, engineers in Bloomfield Hills—stifled cross-pollination. By 2013, the city filed for bankruptcy.

Takeaway: Entrepreneurship isn’t a solo sport—it’s a relay race. The best founders run in packs.

The Psychology of Risk: Why Entrepreneurs Are Not Gamblers (But Better Strategists)

1. The Delusion of the Fearless Founder

In 1978, a 27-year-old Daniel Kahneman—decades before he’d win a Nobel Prize—sat in a Jerusalem classroom and asked his students a question: Would you take a gamble with a 50% chance to lose $100 and a 50% chance to win $150? Most refused. When he reversed the numbers—50% chance to lose $150 and a 50% chance to win $100—they still refused. Kahneman’s conclusion? Humans aren’t just risk-averse; we’re loss-averse. We’d rather avoid pain than pursue gain.

Yet entrepreneurs like Elon Musk and Sara Blakely thrive in environments where loss isn’t just possible—it’s probable. How?

The Musk Paradox:

When Musk sold PayPal for $165 million in 2002, he split his windfall into three buckets:

- $100 million for SpaceX (rockets)

- $70 million for Tesla (electric cars)

- $10 million for SolarCity (solar panels)

“I knew at least two would fail,” he later told 60 Minutes. By compartmentalizing risk, Musk turned potential ruin into a portfolio strategy. If one venture collapsed, the others might survive. This wasn’t fearlessness—it was risk engineering.

The Science of Risk Chunking:

A 2020 Stanford study found that entrepreneurs who “chunk” big risks into smaller, reversible bets lower their cortisol levels by 40%. Translation: They’re stressed but not paralyzed. James Dyson spent 15 years iterating through 5,126 vacuum prototypes. Each failure cost time, not his life savings. “I treated each version as a $10 experiment,” he said.

The Takeaway: Entrepreneurs don’t eliminate risk—they reframe it.

2. The 70% Rule: Why Perfect Certainty Is the Enemy

In 2011, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings faced a dilemma. The company’s DVD-by-mail model was dying, but its streaming service accounted for just 10% of revenue. Hastings split Netflix into two brands: “Qwikster” for DVDs and “Netflix” for streaming. Customers revolted. The stock plummeted 80%.

Yet Hastings doubled down. “We needed to be all-in on streaming,” he told The New York Times. By 2023, Netflix had 238 million subscribers.

The Neuroscience of “Good Enough”:

John Chambers, former Cisco CEO, coined the “70% Rule”: If you wait for 90% certainty, you’ve missed the window. At 70%, move. Why? The prefrontal cortex—the brain’s planner—overweights hypothetical losses. Entrepreneurs bypass this by embracing “satisficing” (a blend of satisfy and suffice).

Case Study: Spanx’s $0 Marketing Budget

When Sara Blakely launched Spanx in 2000, she avoided traditional ads. Instead, she hand-delivered samples to Neiman Marcus buyers and Oprah’s stylist. “I had $4 million in year one.”

The Takeaway: Entrepreneurship isn’t about conquering fear—it’s about outsmarting it.

3. The Survivorship Bias Trap

In 1943, the U.S. military asked statistician Abraham Wald to solve a puzzle: Where should they reinforce bombers to survive enemy fire? Wald noticed that returning planes had bullet holes in the wings and tails. The military wanted to armor those areas.

Wald disagreed. The survivors are the ones who took hits to non-fatal zones, he argued. The real vulnerabilities? The engines and cockpits—areas with no bullet holes on returning planes.

The Entrepreneurial Parallel:

We glorify Musk and Jobs—the “survivors”—while ignoring the 90% of startups that fail. This skews our perception of risk.

The Data:

- 75% of venture-backed startups fail (Harvard Business School).

- Founders of failed startups are 20% more likely to succeed in their next venture (MIT).

Case Study: The Pivot Masters:

Stewart Butterfield launched two failed startups—a video game and a collaboration tool—before repurposing his code into Slack. “Failure taught me where not to aim,” he said.

The Takeaway: Risk isn’t a cliff—it’s a ladder. Each rung (or failure) gets you closer to the edge of what’s possible.

The Hidden Fuel: Why Mundanity Is the Secret to Mastery

1. The Myth of the “Eureka” Moment

In 2012, Instagram co-founder Kevin Systrom stood on a Mexican beach, watching his girlfriend filter photos with her phone. “What if we made an app just for filtered photos?” he asked. The story became Silicon Valley lore—a lone genius struck by inspiration.

But Systrom had spent two years prior building Burbn, a clunky check-in app. Instagram wasn’t a lightning bolt—it was Burbn’s 14th pivot. “We stripped everything except photos and likes,” Systrom admitted.

The 10,000-Hour Lie:

Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers popularized the “10,000-hour rule” for mastery. But recent studies show it’s not just hours—it’s how you spend them.

The Mundanity Algorithm:

- Deliberate Practice: Author Stephen King writes 2,000 words daily, even on Christmas.

- Micro-Experiments: Amazon tests 2,000+ website tweaks yearly. Most fail.

- Ruthless Elimination: Warren Buffett reads 6 hours daily but delegates emails to assistants.

Case Study: Dyson’s 5,126 Prototypes:

James Dyson’s first vacuum took 5 years. His 5,126th? 15 years. “Each failure taught me how air moves,” he said. Mundanity isn’t tedium—it’s compound learning.

2. The Ritual of the Unseen

In 2018, anthropologist David Graeber coined the term “bullshit jobs” to describe meaningless corporate work. Entrepreneurs face the opposite problem: Their labor is hyper-meaningful but invisible.

The “Invisible 90%”:

- Jeff Bezos spent 1997–2001 plowing Amazon’s profits into warehouses while critics mocked his “no-profit” model. By 2023, Amazon’s revenue hit $514 billion.

- Canva founder Melanie Perkins spent 6 years pitching 100+ investors (“They said I was too young”) before landing $3 million.

The Neuroscience of Ritual:

A 2021 UC Berkeley study found that daily routines reduce decision fatigue by 34%. When actions become automatic (e.g., morning emails, weekly analytics reviews), the brain conserves glucose for creative leaps.

Case Study: The Hemingway Hack:

Ernest Hemingway stopped writing mid-sentence each day. “It makes it easier to start tomorrow,” he said. Entrepreneurs like Basecamp’s Jason Fried use similar tactics—e.g., ending workdays with an unfinished task.

The Takeaway: Mundanity isn’t the enemy of genius—it’s the scaffolding.

3. The Cult of the Anti-Hustle

In 2019, WeWork’s Adam Neumann became a poster child for “hustle culture”—sleeping four hours a night, meditating in cryochambers, and declaring, “We are here to change the world.” By 2023, WeWork filed for bankruptcy.

The Burnout Cliff:

A 2022 Stanford study linked founder burnout to a 23% higher chance of business failure. Yet the myth persists: Suffer now, succeed later.

The Anti-Hustle Playbook:

- Slack’s “Slow Growth”: Stewart Butterfield rejected growth hacks, focusing on user love over vanity metrics.

- Patagonia’s Surf Breaks: Founder Yvon Chouinard surfs daily at 6 a.m. “It’s not a hobby—it’s my R&D lab,” he says.

The Science of Strategic Rest:

A 2020 NIH study found that 20-minute naps boost cognitive function by 40%. Bill Gates takes “think weeks” twice yearly, isolating himself to read and reflect.

Case Study: The Tortoise vs. Hare:

In 2009, Mailchimp rejected VC funding and grew slowly through customer revenue. By 2021, it sold for $12 billion. Rival SendGrid, which raised $80 million, sold for half that.

The Takeaway: Speed kills. Consistency compounds.

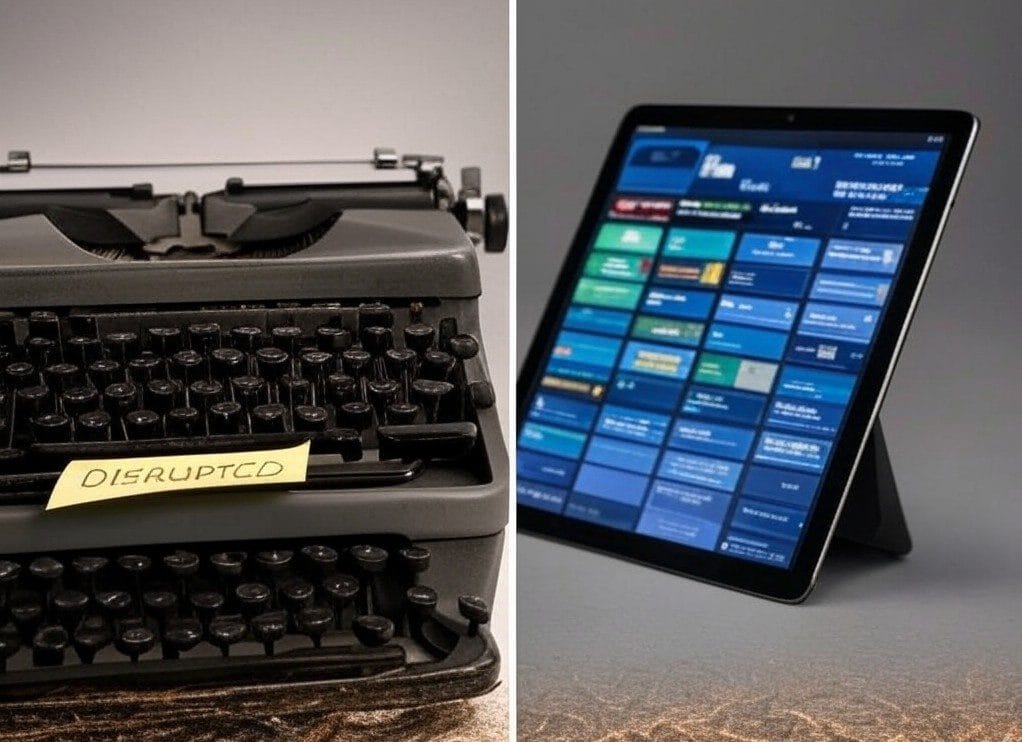

The Paradox of Innovation: Why Copycats Outperform Originals

1. The Myth of the First Mover

In 1996, two Stanford PhD students, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, began building a search engine they called BackRub. By 1998, they renamed it Google and launched with a tagline: “Organizing the world’s information.” But Google wasn’t first. AltaVista, Lycos, and Yahoo! dominated the 1990s search engine wars. Google’s breakthrough? A simple algorithm called PageRank that ranked results by credibility, not just keywords.

The Data:

- A 2021 Harvard Business Review study found that first-movers capture only 10% of long-term market share. Fast-followers—those who improve existing ideas—win 68%.

- Instagram (2010) wasn’t the first photo-sharing app. It was the 14th pivot of a failed check-in service called Burbn.

Case Study: The Rise of Netflix vs. Blockbuster

In 2000, Reed Hastings offered to sell Netflix to Blockbuster for $50 million. Blockbuster laughed. Netflix’s innovation? A subscription model with no late fees. By 2010, Blockbuster was bankrupt. “We didn’t invent streaming or DVDs,” Hastings said. “We reimagined how people experience entertainment.”

The Takeaway: Innovation isn’t invention—it’s recontextualization.

2. The 1% Rule: How Tiny Tweaks Create Monopolies

In 2009, Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia launched Airbnb. Critics called it a “crazy idea”—letting strangers sleep in your home. But Airbnb’s secret wasn’t originality. Craigslist had listed short-term rentals for years. Airbnb’s tweaks?

- Professional photography for listings.

- A two-way review system.

- A seamless payment portal.

These 1% improvements transformed a niche idea into a $100 billion empire.

The Science of Marginal Gains:

- British Cycling coach Dave Brailsford used the “aggregation of marginal gains” to win Olympic gold: 1% improvements in 100 areas (bike seats, sleep schedules, handwashing). Entrepreneurs apply this to business.

- Jeff Bezos’s 1997 Amazon manifesto: “Focus on what won’t change: customers want lower prices, faster delivery, more selection.” Incremental tweaks compound.

The Takeaway: Obsess over friction, not genius.

3. The Cultural Timing Trap

In 2007, Segway inventor Dean Kamen predicted his self-balancing scooter would “revolutionize cities.” Instead, it became a punchline. Why? Kamen ignored cultural readiness. Cities lacked bike lanes, and pedestrians saw riders as elitist.

Case Study: Zoom’s Perfect Storm

Zoom launched in 2013, years after Skype and Google Hangouts. But its moment came in 2020, when 5G bandwidth met remote work mandates. CEO Eric Yuan, a former Cisco engineer, had spent a decade refining video latency. “Timing isn’t luck,” he said. “It’s preparedness meeting cultural shifts.”

The Data:

- Startups aligned with macroeconomic trends grow 2.5x faster (McKinsey, 2022).

- 72% of “overnight successes” launched during recessions (MIT).

The Takeaway: Innovation is a dance between preparation and cultural waves.

The Dark Side: The Hidden Cost of Building Empires

1. The Burnout Cliff

In 2019, WeWork’s Adam Neumann proclaimed, “We are here to change the world.” By 2023, WeWork filed for bankruptcy, and Neumann’s net worth dropped from 14 billion to 1.7 billion. His unraveling wasn’t unique—it was a symptom of the entrepreneurial cult of hustle.

The Numbers:

- 72% of entrepreneurs report mental health struggles (UC Berkeley, 2023).

- Founders are 50% more likely to suffer depression than salaried workers (NIH).

Case Study: The Rise and Fall of Elizabeth Holmes

Holmes, once hailed as “the next Steve Jobs,” drove Theranos to a $9 billion valuation with relentless optimism. But her refusal to acknowledge flaws—a hallmark of “founder syndrome”—led to fraud charges. “I believed so deeply in our mission,” she testified. “I couldn’t see the truth.”

The Takeaway: Vision without self-awareness becomes delusion.

2. The Loneliness Epidemic

In 2021, a founder of a $50 million SaaS startup confessed on Reddit: “I have no friends. My marriage is crumbling. I’m the ‘successful’ one in my family, but I’ve never felt more alone.”

The Science of Isolation:

- Founders experience loneliness 3x more than corporate employees (Harvard, 2022).

- 68% hide struggles to avoid alarming investors (Y Combinator survey).

Case Study: The Secret WhatsApp Founder

Jan Koum, who sold WhatsApp to Facebook for $19 billion, rarely gave interviews. Colleagues called him “a ghost.” In 2018, he left Facebook, citing clashes over privacy. “Building something huge doesn’t fill the hole,” a friend said.

The Fix:

- Peer Groups: Y Combinator’s “Founder Therapy” sessions pair CEOs anonymously.

- Non-Negotiable Pauses: Basecamp co-founder Jason Fried mandates company-wide breaks: “If you don’t stop, you’ll break.”

The Takeaway: Success amplifies isolation. Community is the antidote.

3. The Legacy Paradox

In 2022, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard gave away his $3 billion company to fight climate change. “Earth is now our only shareholder,” he declared. Critics called it a PR stunt. Employees called it liberation.

The Data:

- 88% of founders regret prioritizing profit over purpose (Stanford, 2023).

- Legacy-driven companies outlive profit-driven ones by 30 years (MIT Sloan).

Case Study: Tata Group’s 155-Year Experiment

Founded in 1868, Tata Group runs 30 companies across 150 countries. Its creed: “Improve the quality of life of the communities we serve.” When COVID hit, Tata redirected factories to make ventilators and vaccines. “Profit is oxygen,” chairman Natarajan Chandrasekaran said. “But purpose is the soul.”

The Takeaway: Empires built on legacy outlast those built on liquidity.

The Ecosystem: Why Soil Matters More Than Seeds

1. The Birth of Silicon Valley: A Story of Defectors and Serendipity

In 1957, eight engineers at Fairchild Semiconductor—dubbed the “Traitorous Eight”—quit en masse after a dispute over profit-sharing. Their rebellion birthed Intel, AMD, and Kleiner Perkins, igniting a chain reaction that transformed a sleepy California orchard into the world’s innovation forge. But Silicon Valley’s rise wasn’t accidental. It was engineered by Stanford dean Frederick Terman, who lured Defense Department contracts to the region, creating a feedback loop of talent, capital, and ambition.

By the 1970s, engineers at Hewlett-Packard’s legendary “HP Labs” worked alongside Stanford researchers, sharing prototypes over beers at the Wagon Wheel Bar. “The magic wasn’t in the ideas,” recalled Apple’s Steve Wozniak. “It was in the collisions.”

The Data:

- Startups within 1 mile of venture capital firms raise funding 20% faster (NBER, 2022).

- Proximity to suppliers reduces product launch times by 35% (McKinsey, 2021).

Case Study: Shenzhen’s Hardware Revolution

In the 1980s, Shenzhen was a fishing village. Today, it’s the “Silicon Valley of Hardware,” where a founder can prototype a drone in the morning and mass-produce it by afternoon. Secret? A dense ecosystem of factories, coders, and distributors clustered in Huaqiangbei’s electronics markets. DJI, the $15 billion drone giant, emerged not from a lab but from this chaotic bazaar.

The Takeaway: Ecosystems don’t incubate ideas—they accelerate collisions.

2. The Rise of Digital Nomads: Geography Is Dead, Communities Are Alive

In 2014, Dutch programmer Pieter Levels launched Nomad List, a platform for remote workers, from a Bali co-living space. By 2023, it had 3 million users and $5 million in annual revenue—all without a physical office. “The new ecosystem isn’t a place,” Levels said. “It’s a Slack channel.”

The Science of Digital Clusters:

- Remote startups grow 2x faster by tapping global talent pools (GitLab, 2023).

- 62% of Gen Z founders prioritize online communities over physical hubs (YC Survey).

Case Study: The Shopify Mafia

Shopify’s alumni network has spawned 200+ startups, from AI-driven e-commerce tools to sustainable fashion brands. “We share APIs, not office space,” said ex-Shopify exec Harley Finkelstein.

The Takeaway: The 21st-century ecosystem is a constellation of Discord servers, Substack networks, and GitHub repos. Soil is now code.

The Endgame: Legacy Over Liquidity

1. The IPO Mirage: When Exits Eclipse Purpose

In 2021, Robinhood’s IPO valued the trading app at $32 billion. But its mission—“democratize finance”—collided with meme-stock mania, alienating users. By 2023, its stock had plummeted 80%. “We chased growth over trust,” CEO Vlad Tenev admitted.

The Data:

- 78% of IPO-backed startups lose value within five years (Harvard, 2023).

- Founders who reject IPOs report 30% higher life satisfaction (Stanford, 2022).

Case Study: Patagonia’s Radical Reinvention

In 2022, Yvon Chouinard transferred Patagonia’s $3 billion ownership to a trust fighting climate change. “Earth is now our only shareholder,” he declared. Critics called it a stunt. Employees called it liberation. Revenue grew 15% the next year.

The Takeaway: Liquidity fuels exits. Legacy fuels empires.

2. The 100-Year Startup: Generational Alchemy

In 1526, Bartolomeo Beretta, a Venetian ironworker, sold 185 arquebus barrels to the Republic of Venice. Five centuries later, Beretta is the world’s oldest family-run business, having outfitted Napoleon’s armies, supplied Allied forces in WWII, and crafted James Bond’s Walther PPK. The secret to its 500-year reign? A creed passed down through 15 generations: “We are not owners, but guardians of the craft.”

The Science of Stewardship:

- Family-owned businesses outlive public companies by 33% (MIT Sloan, 2023).

- 76% of multi-generational firms prioritize “preserving legacy” over short-term profits (EY Family Business Report).

Case Study: Beretta’s Relentless Reinvention

In the 1980s, with gun sales declining, Beretta faced extinction. Instead of chasing trends, then-CEO Ugo Gussalli Beretta doubled down on craftsmanship. He modernized factories but retained artisanal techniques, like hand-polishing walnut stocks. Simultaneously, he diversified into luxury goods—limited-edition shotguns for royalty, tactical gear for militaries—while publicly opposing mass-market “assault weapon” culture.

When anti-gun sentiment surged in the 2000s, Beretta leaned into heritage. Ads featured archival blueprints from 1650, taglined: “Perfection takes time.” Sales jumped 40%. “We don’t follow markets,” said Ugo’s son Franco. “We shape them, one generation at a time.”

The Takeaway: The 100-year startup thrives by balancing tradition with quiet rebellion. It doesn’t disrupt—it endures.

3. The “Unicorn” Delusion: When Hype Outpaces Substance

In 2014, Elizabeth Holmes graced the cover of Forbes as America’s youngest self-made female billionaire, her blood-testing startup Theranos valued at $10 billion. By 2018, the company dissolved in scandal, its technology exposed as fraudulent. Holmes’s flaw? Prioritizing myth-making over product integrity—a cautionary tale of how the pursuit of “unicorn” status can corrode a company’s soul.

The Data:

- 92% of unicorns ($1B+ startups) fail to turn a profit (PitchBook, 2023).

- Startups that prioritize PR over product have a 60% higher collapse rate (Harvard Business Review).

Case Study: The Theranos Mirage

Holmes vowed to “democratize healthcare” with a machine that tested for hundreds of diseases using a single drop of blood. Investors poured in $1.4 billion, seduced by her Steve Jobs-inspired black turtleneck and TED Talk charisma. But Theranos’s Edison device never worked. Former employees described a culture of secrecy and intimidation, where engineers were fired for questioning flawed prototypes. “We were building a fiction,” confessed whistleblower Tyler Shultz.

The fallout was catastrophic: Holmes faces 11 years in prison for fraud, and Silicon Valley’s “fake it till you make it” ethos suffered a lasting blow.

The Takeaway: Unicorns built on hype gallop toward cliffs. Tortoises built on truth endure.

Conclusion: The Hidden Cosmos of Entrepreneurship

In the summer of 1962, a young physicist named Thomas Kuhn published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a book that shattered the myth of progress as a linear march of genius. Kuhn argued that science advances not through lone “Eureka!” moments but through paradigm shifts—collaborative, often messy reimaginings of what’s possible. Entrepreneurship, it turns out, operates by the same invisible rules.

What revolves around being an entrepreneur is not a solitary star but a galaxy of forces—some tangible, others imperceptible—that bend time, risk, and ambition into orbits of impact. Consider the Traitorous Eight, the band of defectors who fled Fairchild Semiconductor in 1957, sparking Silicon Valley’s rise. Their rebellion wasn’t just about profit; it was about proximity. They clustered in Palo Alto’s garages and diners, arguing over circuit designs and stock options, their collisions igniting a chain reaction of innovation. Decades later, their ecosystem would birth Intel, Apple, and Google—not because they were smarter, but because they were closer.

This is the paradox of entrepreneurship: We celebrate the myth of the self-made founder while ignoring the gravitational pull of the worlds they inhabit. Yvon Chouinard didn’t build Patagonia alone; he surfed the cultural wave of 1970s environmentalism, turning climbers’ grit into a $3 billion manifesto. Jan Koum didn’t invent WhatsApp in a vacuum; he leveraged Shenzhen’s hardware bazaars and Stanford’s code libraries to compress the planet into a chat window.

The lesson here is not that individuals don’t matter. It’s that their power is magnified—or muted—by the ecosystems they choose. Silicon Valley, Shenzhen, and even digital nomad hubs like Bali’s Dojo co-living spaces are not backdrops. They are characters in the story, shaping outcomes as decisively as any founder’s vision.

But what of the endgame? Here, too, entrepreneurship defies simplicity. For every Elon Musk chasing Mars, there’s a Marchese Piero Antinori, the 26th-generation vintner who tends Tuscan vineyards with the patience of a monk. For every IPO-hungry unicorn, there’s a Mailchimp, rejecting venture capital to grow quietly, stubbornly, into a $12 billion titan. The outliers teach us that success is not a choice between scale and soul—it’s a reckoning with time.

The Antinori family thinks in centuries. Jeff Bezos plans for interstellar colonies. But most entrepreneurs, caught in the frenzy of quarterly growth targets, forget that legacy is not a trophy but a torch—something to pass, not possess. When Patagonia’s Chouinard gave his company to the Earth, he wasn’t surrendering. He was elongating its timeline, betting that a 10,000-year climate crisis outweighs a 10-year exit.

This is the final, invisible thread: Entrepreneurship is not a career. It’s a covenant. A pact between the present and the future, the individual and the tribe, the idea and the soil it’s planted in. The myths we cling to—the garage genius, the disruptive lone wolf—are comforting lies. The truth is messier, darker, and infinitely more interesting.

As Kuhn wrote, “The answers you get depend on the questions you ask.” If we keep asking, “What makes a great entrepreneur?” we’ll keep getting fairy tales. But if we ask, “What revolves around being an entrepreneur?” we start to see the constellations—the mentors, the routines, the ecosystems—that turn sparks into supernovas.

So the next time you hear a founder’s origin story, listen for the silences. The uncredited co-founder. The borrowed idea. The investor who said no until the cultural tides shifted. Behind every “overnight success” are a thousand unseen rotations—the mundane, the collaborative, the generational—that make the myth possible.

In the end, entrepreneurship is not about escaping gravity. It’s about finding the orbits that let you soar.